Political Suicide?

Postwar Japan’s constitution was drafted by the US occupation force, only to be slightly revised by the Japanese Government before its enactment in 1947.

For obvious reasons, many resented the idea of keeping a constitution that was virtually imposed by foreign occupiers, and the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) was no exception.

In fact, one of the reasons behind the LDP’s formation was pursuing a Japanese-made constitution, thereby gaining support from the conservatives and patriotic right.

This is actually still true today, as the LDP periodically reminds their constituents of their ultimate goal of constitutional revision, but 70 years of unfruitful efforts seem to have reduced such appeal into a mere rallying cry.

Then why haven’t these attempts succeed in the first place? ,

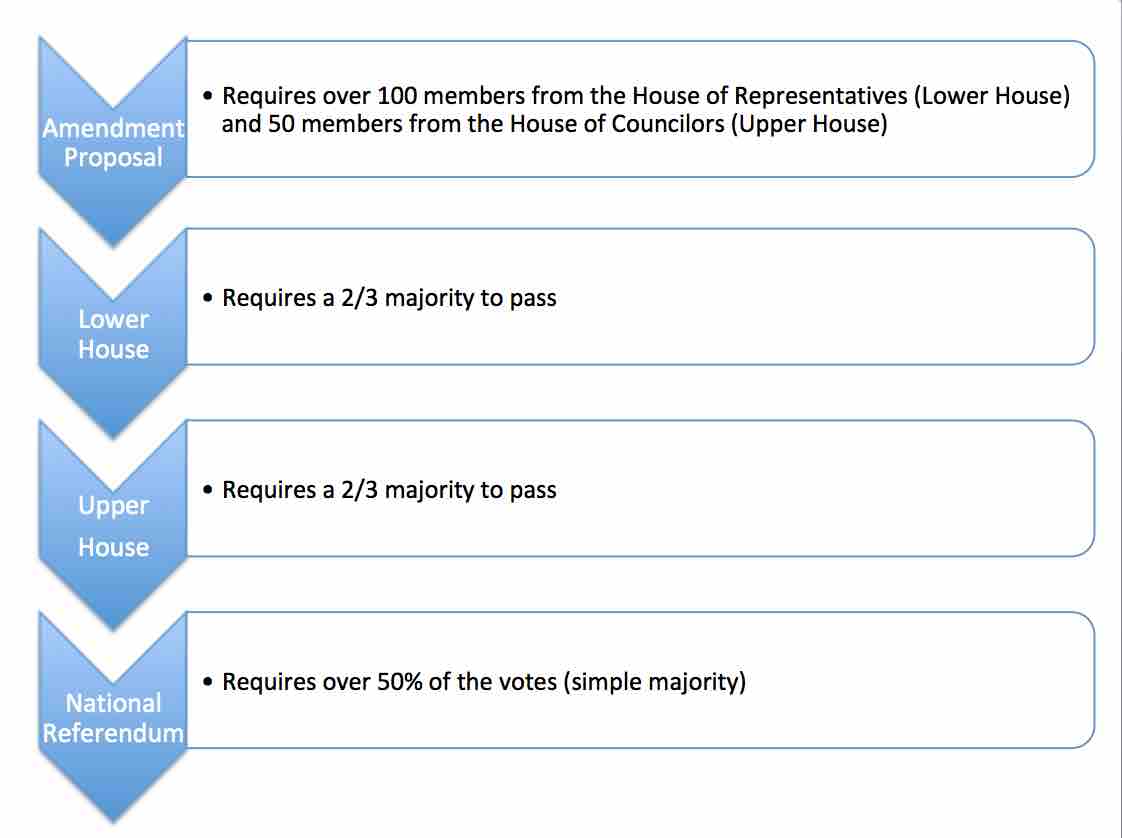

Although Article 96 of the constitution lays out the necessary procedures for revision, the political reality indicates such amendment as nearly impossible.

The first step, submitting the amendment draft, is not that much of a hurdle since it only requires 100 and 50 members respectively from the House of Representative and the House of Councilors.

However, the next step is the most challenging, as one would need a 2/3 majority in both houses of the Diet to initiate a national referendum.

Based on simple math, parties aiming for constitutional reform would need 66% of the seats in both houses which is an absurd number.

For reference, the largest percentage of seats ever gained by the LDP was 64% in the 1950s〜60s with recent ratios flying in the 50〜55% zone.

In retrospect, if the LDP invested all their political resources and fully pushed towards amendment in the 1960s, they might have well succeeded in their goal.

But, this would have come at a high cost considering the fact that the 1960s were one of the most politically turbulent eras with the leftist factions frequently clashing with riot police in broad daylight.

Had the LDP prioritized constitutional reform amidst such environment, the country would have seen further violence and political division.

LDP’s Fading Enthusiasm

So, the LDP took a different approach instead of clashing head on with the opposition factions.

They sought economic growth to satisfy the silent majority first.

This approach turned out quite well, by alienating the leftist factions from the public majority, and bringing the “economic golden age” to a defeated nation.

Due to this accomplishment, the LDP gained wide public support and managed to maintain its status as the ruling party throughout the Cold War period.

And it is exactly this period of unopposed governance where the LDP transformed into a power hungry party where they strived to cling on to their position rather risking any political downfall.

When one enjoys the benefits only available to the ruling party, it is understandable for them to become evasive towards any change or risk.

As such the LDP’s appetite for revising the constitution started to wither.

Compromise With The Left

The leading opposition party, the Socialist Democratic Party (SDP), also exacerbated this lukewarm attitude.

The SDP was a leftist party who gathered support by opposing any constitutional amendments, especially that of Article 9. Therefore, the SDP would only require a 1/3 minority to achieve this task.

This enabled the LDP and SDP to reach a tacit compromise when engaged in politics, turning the parliament into a fixed match or political setup.

The LDP, obsessed with governing, wanted to secure a simple majority, whereas the SDP only required a 1/3 minority to satisfy their ideological support base.

To be clear, the elections were certainly not rigged, but there was a general understanding that the seat allocation between the LDP and SDP would end up being 2 :1.

Revision Unnecessary?

Today, the political landscape is vastly different from the Cold War era.

While the LDP preserved their dominant influence, the SDP has ceased to exist, and the main opposition parties do not pose any serious threat for the time being.

Moreover, Chinese military expansion, North Korea’s nuclear development, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have significantly altered the atmosphere regarding security issues.

Given the deteriorating security environment, the constituents are much more pragmatic and even acceptable towards revising Article 9.

If the LDP fully capitalizes on this sentiment, they might have a good chance of finally accomplishing their long-held ambition. Theoretically speaking, the LDP could persuade other likeminded parties who favor constitutional amendment, thereby achieving the 2/3 threshold.

But, uniting these parties would prove to be challenging since their interests only converge in the general direction. The LDP wants to focus on Article 9 whereas some parties prioritize revising other parts of the constitution.

Adding to this difficult coordination, any attempt would experience fierce resistance from the remaining leftist factions. Despite being on their last leg, the move might possibly revitalize the declining left, giving them some political momentum.

The issue would certainly be attributed to WW2 memories, instead of present security concerns, invoking anxiety among the public and meriting the left as a whole.

When Shinzo Abe sought new security legislations back in 2015, his administration was met with substantial resistance from the left – sizable protests in front of the PM office and parliament claiming the new bill would bring Japan into war.

The scale and magnitude of these movements were nothing compared to the 1960s and 70s, but it did generate a considerable drop in Abe’s approval ratings.

If Shinzo Abe, arguably postwar Japan’s most powerful Prime Minister, faced such backlash in merely enabling the limited use of collective self-defense, any move for constitutional amendment would be detrimental for future leaders.

One would simply exhaust all of his/her political resources, dividing the nation and rendering the administration vulnerable afterwards.

The last thing the LDP would want is a recuperated leftist movement that could divide the public based on old political boundaries.

On a more interesting note, the current LDP administration doesn’t need constitutional revision to implement more security reforms.

Ironically, 70 years of circumventing Article 9 has proved that Japan can actually enhance its military by merely reinterpreting the clauses. This somewhat sneaky way has enabled Japan to continuously update its defense capacity, to the extent where the Self-Defense Forces operate long-range missiles and light carriers.

If one can further develop its military capability without amendment, why take the political gamble of risking the incumbent seat?

Comments