Federation of Landlords

With the arrival of the US fleet in 1854, Japan was compelled to abandon its two and a half century-long isolationist policy and open up to commerce.

This eventually led to the Meiji Restoration where a new government sought to prevent any foreign incursions by rapidly modernizing the country. For such modernization or “Westernization” efforts to work in the first place, it was crucial to unify the loose federation of clans into a single nation state.

We first need to understand that Japan back then was a feudal state comprised of nearly 300 clans or local samurai landlords with the Tokugawa Shogunate as their dominant leader.

Contrary to the word’s impression, the Shogun was far from a dictator or supreme ruler, and was merely the head of the samurai landlords (daimyo) whose actual authority fluctuated throughout the course of history.

The last decades of the Tokugawa Shogunate saw its influence dwindling as the surrounding environment became more turbulent, resulting in the final blow at the Battle of Toba-Fushimi.

By 1868, the Shogunate had effectively ceased to exist and a new government under the name of the Emperor was formed. This Meiji Government was primarily consisted of low to medium ranking samurais who put the task of building a strong nation state in front of the loyalty to their respective daimyos.

But, even with this change in political leadership, the feudal structure remained intact since the newly born government could not yet coerce the daimyos in surrendering their power.

The Meiji Government confiscated land from the Shogunate and their allies, but were still stuck with over two hundred daimyos who either sided with the Emperor or surrendered early enough.

Two Decrees

As the first step towards centralization, the Meiji Government issued a decree in 1869 that returned the land and residents from the daimyos to the Emperor.

However, this was superficial in reality and most daimyos continued to rule their territories as newly appointed governors.

So, what was the point of such move if nothing essentially changed?

Well, it is said that this was a trial balloon in testing the daimyos’ reaction, which actually hinted the feasibility for radical political reforms.

After witnessing zero resistance, the Meiji Government decided to speed up the process while simultaneously building up a military dedicated to the Emperor.

The initial unit of 10,000 men was a combined force of samurais from the Satsuma, Choshu, and Tosa clans (the Big Three who defeated the Shogunate Regime), and was both well-equipped and battled hardened enough to suppress potential rebellion.

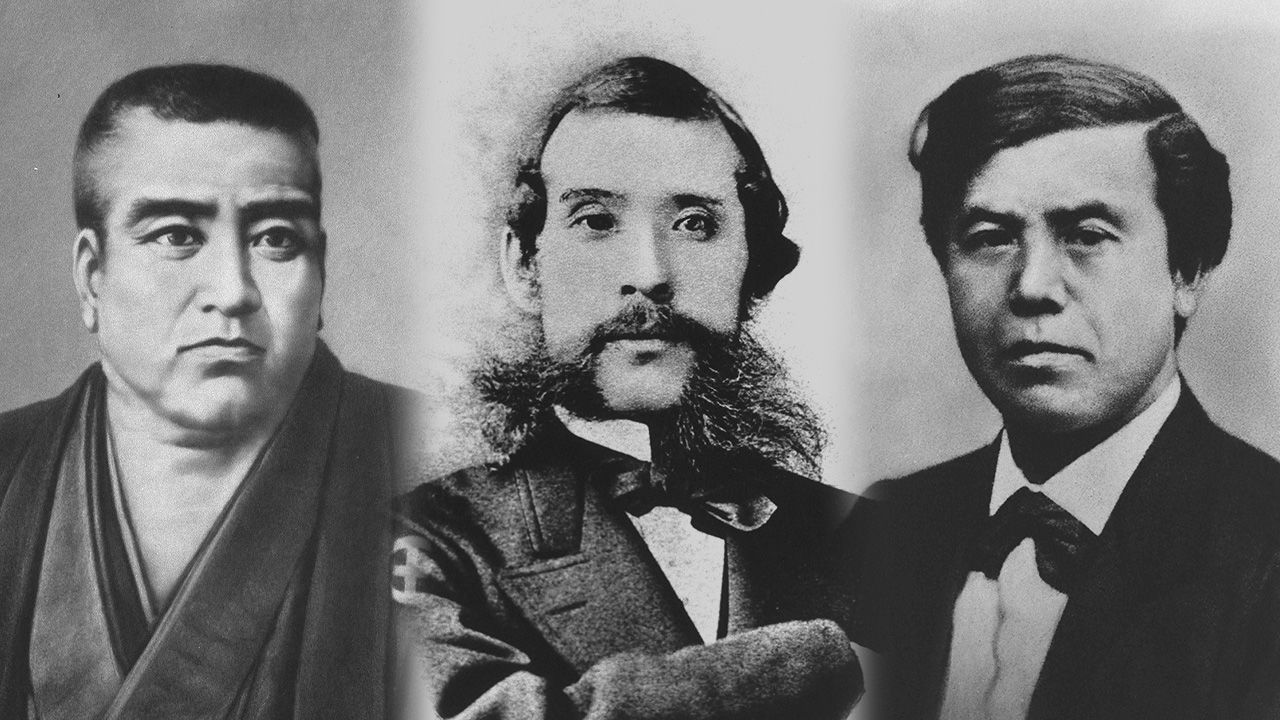

Saigo, Okubo, Kido – the main figures of the Meiji Restoration

Saigo, Okubo, Kido – the main figures of the Meiji Restoration

The government made its final move in 1871, with the Imperial Proclamation of abolishing the clans and replacing them with prefectures. The daimyo governors were to be replaced by bureaucrats sent from the central government.

Unlike the previous decree, this act would effectively take away any remaining authority from the daimyos, marking an end to the feudal system.

As the Imperial Units awaited for possible insurrection, the major daimyo governors were summoned to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and notified of the decision.

Surprisingly, no one resisted or outright objected to the decree, despite it forced them to abandon their inherent territories and landlord positions. The only person who explicitly performed his dissatisfaction was in fact the Satsuma daimyo, Hisamitsu Shimazu.

Hisamitsu misunderstood that he would eventually gain a position similar to that of a Shogun and agreed to contribute the bulk of his forces to the aforementioned Imperial Unit.

When this expectation ended up as nothing more than an illusion, he protested by shooting fireworks at his residence all night, but that was all he did.

In this manner, the Meiji Government managed to dissolve the feudal structure with a single decree, meeting virtually no resistance at all.

Comments