Last Safe-Haven?

Recent years have seen Western culture including Hollywood films being criticized for facilitating too much narrative, or in other words, pursuing “political correctness.”

While this remains a controversial topic, it seems from an outsider’s view that the entertainment industry has somewhat become afraid of lacking diversity or at least seen as such.

Of course, an industry as influential as Hollywood (and other entertainment giants ) should be considerate of cultural representation as it would definitely inspire countless people across the globe.

But, that doesn’t mean they should always prioritize diversity over the core principle of producing good stories.

Take Star Wars for an instance.

The absolute majority of the fanbase just wants good story-writing. As long as the script is well-thought and corresponds with the existing Star Wars universe, nobody cares what gender the characters represent.

Unfortunately, bad-scripts have become a trend in the recent Star Wars industry, disappointing numerous fans just as many other franchises have done so in the same manner.

In light of all this development, Japanese anime and manga culture seems to be untouched by this political correctness phenomenon. Some are even calling it one of the last safe-havens for freedom of expression.

While most of these claims are exaggerated, it does contain some truth.

Japan’s anime industry enjoys more freedom or at least receives less criticism from its audience or the media regarding diversity, cultural representation etc.

So, why is this?

Japanese Are Apolitical

Firstly, Japan is close to a homogenous society with nearly 95% being the traditional Japanese or Yamato Japanese.

There are indeed ethnic minorities such as the Ryukuans (Okinawans), Ainu, and Korean descendants, but these groups have integrated into society quite well (way better than other cases around the world).

Such demographics mean racial diversity is not considered important when producing anime since no one would voice concerns in the first place.

In addition to this social demographics, the majority of Japanese are apolitical, possessing little opinion towards political issues. Indeed, there is a tacit understanding to refrain from discussions politics and religion at the workplace or while drinking, as it would generate division rather than unity.

Asides from this cultural atmosphere, the three-decade long stagnant economy has made the public somewhat lethargic compared to the politically volatile 1960s~70s.

This trend is especially examined among the younger generation, whereas the senior generation around the ages of 70〜80 remain quite active in a political sense. Most rallies, which are often held by the leftist factions, are consisted of old people who certainly remember the nostalgic days of their youth.

On the contrary, the younger generation, who form the main bulk of anime viewers, hold a lukewarm attitude towards politics since the 30 years of LDP leadership and the failures by the opposition parties provide little hope for the future.

Needless to say, when the people are politically unenthusiastic, there is little chance they would attribute entertainment to such aspect.

Thus, Japanese do not care whether the anime or manga represents diversity or not. They simply enjoy it as a piece of entertainment, with any political ideology absent when watching.

Simply put, Japanese viewers evaluate the anime based on its actual content rather than the overall agenda (as it should be in the first place).

This does not mean anime is purely non-political. Surely, Japan has recently seen the rise of “progressive” activists who advocate for cultural appropriation. Yet, compared to the United States, they are limited both in size and influence.

Anime and manga does come under their scrutiny time to time, raising certain issues, but their outcries are usually met with cold reception from the absolute majority whom just want to enjoy the entertainment without politics.

When your viewers start to notice the overly exposed easter-eggs instead of diving into the story itself, it makes it rather difficult to deliver your message as the audience would become fed up and leave the theater.

This leads to our next argument, just write good content first.

Just Write Good Stories.

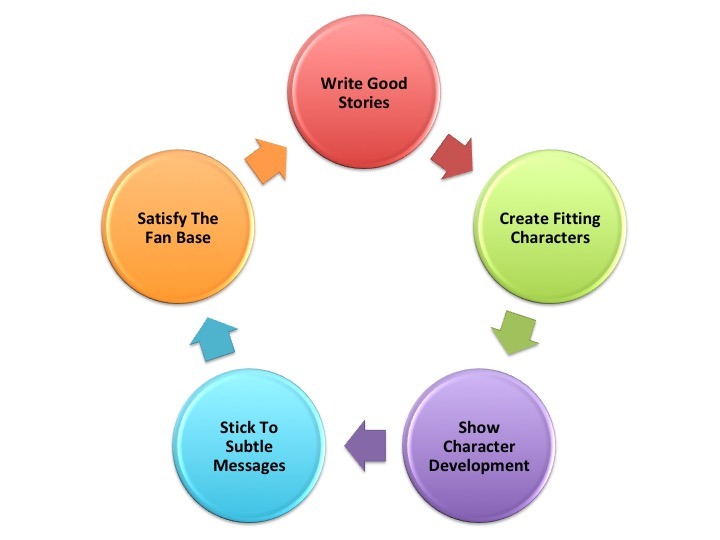

If the recent comparison between anime and aforementioned Western entertainment has taught us anything, it is the mere fact that it is possible to create a popular, strong character without openly promoting a certain agenda.

As long as the content has good story-telling alongside likable characters based on interesting backgrounds or character development, the audience will be on board regardless of the main character’s gender, race or whatever else.

Just check each season’s anime lineup. It is full of female characters who are portrayed as strong, capable beings without overt expression or at the expense of other characters.

For instance, the fall-winter season saw two animes exceed expectations in terms of popularity : (1) Frieren Beyond Journey’s End and (2) The Apothecary Diaries.

Both were led by strong and highly-skilled, but amusing female main characters with well-though background stories.

Or even take another example like Golden Kamui, a manga/anime that illustrates the Ainu culture in an unprecedented scale.

The leading character is a smart young girl belonging to the ethnic minority, who is likable not because of her gender, but by her sense of humor, expertise of the wilderness, amazing abilities, and interesting background story.

Neither Golden Kamui, Frieren, nor Apothecary Diaries have to over-emphasize their gender or ethnicity to attract the audience. They succeeded in selling whatever message to the viewers/readers by simply providing a thorough story and character.

When watching these episodes, there is no cringe or the feeling of something being off because the anime simply focuses on story-telling and character development.

These are just a few recent examples, but it does highlight the following nature of anime – strong and likable female characters without relying on conspicious narrative, but achieving popularity through subtly.

To sum up, Japanese anime are free from political correctness not only because the audience are apolitical, but because they can generate a positive cycle that enables the audience to enjoy an appropriate character without intentionally pushing for such agenda.

No need for full-blown promotion, just write good scripts and sparkle some hidden messages without obstructing the story – it’s really that simple.

So long as you produce good content entertainment wise and stick to this basic principle, any message you wish to convey will be accomplished spontaneously.

-320x180.jpg)

Comments