Building Offensive Capabilities

Faced with a confident China flexing its muscles near Japanese waters, the island nation is responding by heavily investing in its Self-Defense Force (SDF) with the largest defense budget ever approved.

This includes building up offensive capabilities for the first time in postwar history, a significant breakaway from the long-held tradition of passive defense or absolute defense-oriented posture.

Mostly owing to the pacifist Constitution that prohibits the possession of military force, postwar Japan has always struggled to circumvent this ban in nearly every aspect of national defense.

Japan invented clever interpretations, such as defining military force as something different from a minimum force necessary for self-defense, and succeeded in forming a formidable de-facto military.

But, even such cunning tricks could not open the door for offensive capabilities, deriving the SDF of any decent counterstrike weapons.

Although the SDF could intercept enemy missiles or aircrafts, they were unable to strike the origins of such attacks in both a legal sense and capability-wise. All Japan could do was to outlast the air-raids and wait for the United States to deliver counterstrikes.

This stance became viewed as ludicrous as time went by, and the continuous nuclear threats by Pyongyang along with Beijing’s rapid military buildup was enough to persuade the public for a drastic change.

Hence, Japan decided to acquire offensive capabilities or counterstrike weapons to nullify enemy bases instead of passively awaiting their missiles.

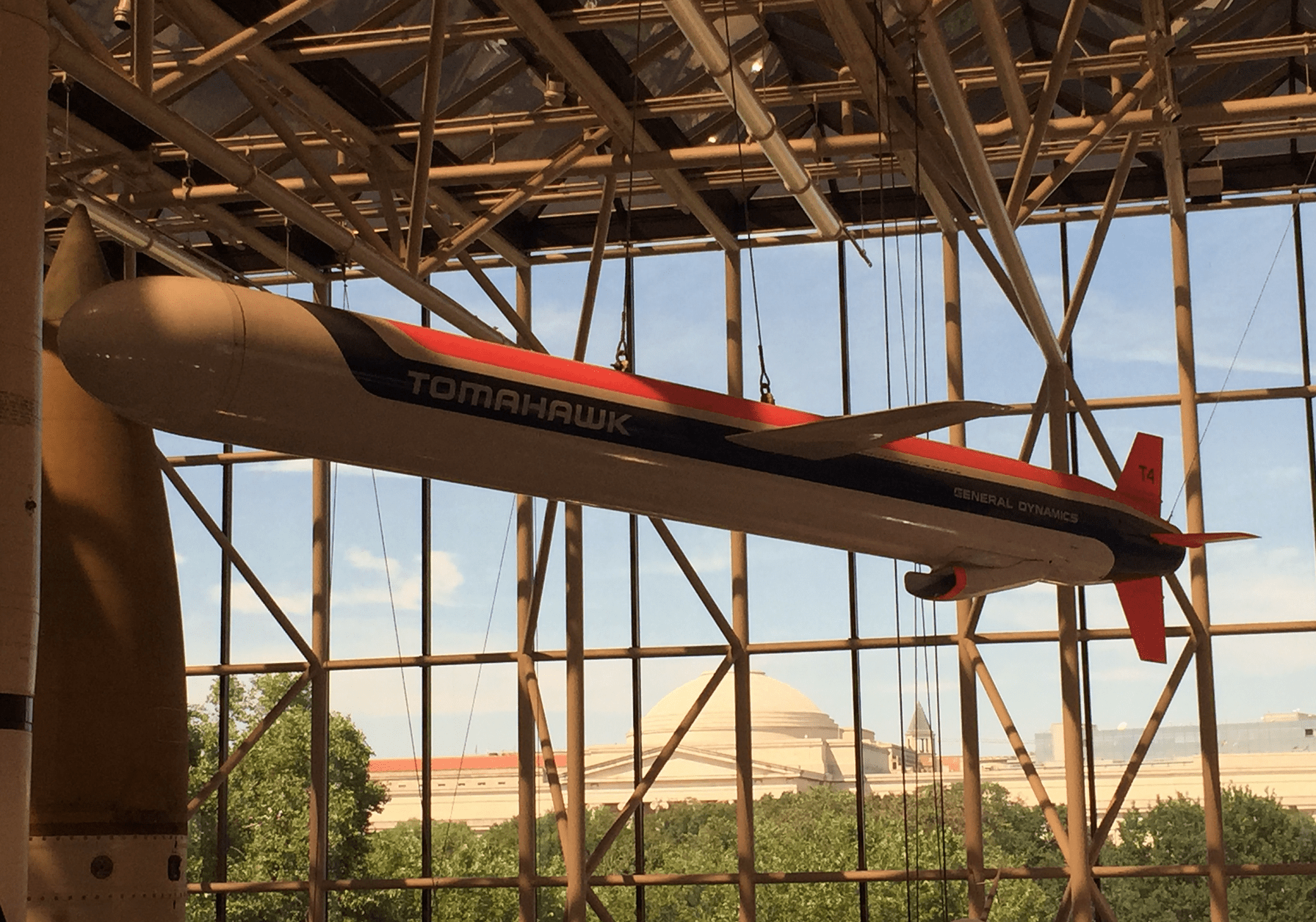

Quick, Easy, Reliable Tomahawks

Despite such political decision, the SDF literally had to build these capabilities from scratch.

Aside from several types of rockets and missiles, intended for invasion forces on Japanese soil, the only weapon SDF could rely on was the JDAM guided bombs dropped from F-2 fighter planes.

Even this scenario was somewhat far-fetched since they had little experience in coordinated airstrikes, let alone targeting enemy territory.

In order to build upon this close-to-zero capacity, Japan embarked on a two-track policy of domestic production and introducing foreign weapons. While new made-in-Japan missiles are undergoing development, Tokyo ordered 400 Tomahawk cruise missiles for immediate counterstrike abilities.

The reputation of being accurate and reliable was enough to make Tomahawks a prime candidate, but it was also deemed as a relatively easy task as well as instrumental in facilitating interoperability.

The SDF already operates a variety of American military hardware and software, including the vertical launch system that is compatible with the Tomahawk missiles.

Thus, the SDF could start using these missiles with minimum modifications to their operating system.

A Mutually Beneficial Solution

Adding to this prospect of a quick, easy acquisition of offensive capabilities, the use of Tomahawks will allow coordination with the US military, which is necessary for the inexperienced SDF to conduct effective operations.

In other words, the Tomahawk missiles were the easiest, quickest, and most viable option in ensuring counterstrike capabilities within the Japan-US alliance structure, not to mention the purchase being beneficial to the US.

Considering the attritional nature of modern warfare, 400 Tomahawks are hardly enough for actual conflict, and many more is expected to be added on Tokyo’s wishlist.

With more Americans casting doubt on the US role as a global security enforcer, the likelihood of future purchases can at least “please” those in Washington to some extent.

Therefore, the purchase is mutually beneficial with Tokyo swiftly gaining the much needed capabilities whereas Washington can expect Japan as their customer for further weapons sales.

Comments